Going in Social Circles: Meeting People in New Places

I’ve just moved to a city several thousand miles from home. I am all set-up with my own place and have settled into my new job. I am enjoying exploring Beijing’s streets, galleries, cafes, and shops – I spend a lot of my free time wandering around on my bike or on foot, getting my bearings and seeing new places.

I’m not unhappy, but I spend a huge amount of time alone. I simply don’t know many people.

I have a few ‘useful’ contacts I can depend upon if ever I find myself in need of help, and I am lucky to have several interesting and friendly colleagues.

But I can’t think of a single person I know who wants their social circle dictated by their line of work, nor who wants to socialise with the same 6 people 24/7.

Which is why I’ve pursued every interesting contact I have managed to get my hands on. I’ve met friends of friends, ex-students of my boss and colleagues, and enrolled in a language course through which I’ve met a classroom full of interesting people from all over the world – Mongolia to Iran, Australia to Switzerland.

Being an expat brings a particular set of challenges, including the obvious language barrier and the problem of constant migration. The population of non-Chinese people in China is vast but changing fast. Some people come here as students and leave after as little as 2 months, whereas others are still here 9 years later without a clue as to what made them stay.

The issue, though, is that people are always leaving. I’ve been here less than 3 months and I’ve already been to a leaving party.

Long-term expats build up a strong friendship group only to watch it slowly disintegrate over time. Those who don’t find love in China (whether it be a partner, an ideal job or way of life) tend to leave eventually.

It’s simply part of ex-pat life: moving onward or homeward is inevitable.

Ebb and flow is therefore the model we live by. Getting too settled is never really an option, particularly in such a rapidly developing country, which means adaptability is key to happiness. Unless you plan to live as a hermit, meeting new people is a constant requirement of Beijing life, no matter how long you’ve been here for.

But how?! Colleagues, friends’ friends, ex-students and language courses aren’t exactly bottomless supplies of people, nor do they necessarily yield the relationships you hope to forge. There’s got to be another way to tackle my dilemmas, namely: a lack of girl-friends and ‘where do I find more Brits?’

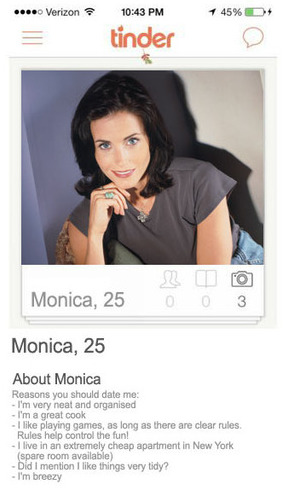

Yep, you guessed it: Tinder.

(Image via)

Ok, so maybe Tinder isn’t the most obvious choice for forging actual, long-term friendships with people. The majority of people who use Tinder on home turf are only out to get one thing – those people who swipe right to EVERYONE and others who send penis pictures as soon as you get past ‘hello’…

That is true of some people using it overseas too, but there’s something different about China’s Tinder scene.

In a city where foreigners face a constant culture- and language-barrier, Tinder provides direct access to the English-speaking community – for both expats and young Chinese people. The stigma Tinder carries elsewhere does transfer (going on a ‘Tinder date’ automatically provokes people to ask ‘isn’t it just for hook-ups?’) and prevents some people from accessing what is essentially an instant network of potential contacts.

There are fewer sexpectations and a more relaxed attitude to making friends.

It’s simply another social network.

One hurdle: Tinder is blocked in China.

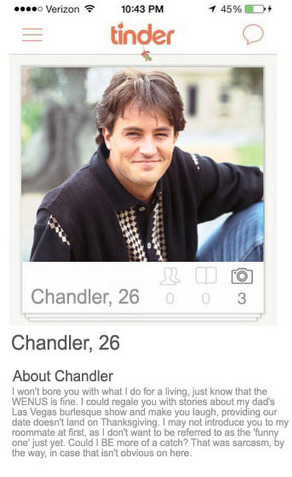

Because it requires Facebook to log-in, everyone on Tinder has to use a VPN to access it. Now, that’s not a huge problem, as the majority of young people (local and foreign) use a VPN to access world news and other social networking sites (even the British Ambassador admits to using a VPN). But it does mean access is pretty patchy and frustrating – we probably all recognise the phenomena of getting a notification then being unable to actually read the message – so it necessitates a certain determination of its users.

(Image via)

With access being so patchy, people tend to exchange contact details more readily than they otherwise would, and perhaps is a good idea. Anonymity doesn’t last long and trust is a necessity. Wechat (the Chinese messaging alternative to Facebook & Whatsapp) is a pretty useful alternative though, as it doesn’t require you to give out a phone number.

When it comes to meeting people, staying safe is more imperative than ever – when you live alone in a foreign city you don’t know, simply telling the taxi driver your address is a challenge – it’s harder to get out of a sticky situation without the support network or infrastructure of the social services that you might have back home.

Thus far, I have met with two of my Beijing Tinder ‘matches’. The first was a disappointingly awkward date with someone surprisingly cocky for his nerdiness, whom I shall not be seeing again.

The second was an enlightening coffee in an converted old European church with a documentary photographer doing a project on Tinder users in China… who of course prompted this post, and I shall be seeing again. Funny how things work out!

If you enjoyed this post, why not check out ‘Dating Etiquette: Virtual Judgement‘?

Tags: friendship Joy Tinder Travel

Categories: Adventureland