Endometriosis: 176 million women suffer from it, but how many know it exists?

In my first few days of university I met a bright, bubbly girl while I was out on a pub-crawl. She had crazy curly hair, wore glasses and she was on the same degree course as me. We spoke at high speed back and forth for hours that night, and for many nights thereafter. We took classes together. We would sit in one of our dormitory kitchens drinking tea (hers weak, mine strong) while we discussed poetry.

By the time we reached second year, we two were virtually inseparable. We didn’t live together but might as well have. People on our degree course referred to us as a pair; they’d hardly ever seen us apart. We shared everything, good and bad, laughter and tears. I felt like the sister she’d never had.

We kindled our mutual tea drinking obsessions (we could share a teabag and both get a perfect cuppa, exactly how we liked it) talking for hours about novels and boys and plays and roommates and exams and lecturers. I felt that a problem shared with her was more than halved, she always had a solution to help me. I sensed I was learning more from her than from going to my classes.

There was something, though, I didn’t quite understand about my best friend. This friendly, sociable woman would disappear for a few days every so often. On a Friday evening I’d realise I hadn’t seen her since Monday, and wonder where she’d been. I would hope, desperately, that she still wanted my friendship. Later she would reappear and we’d click right back into our high-speed conversations. But I still hadn’t understood where my friend had gone to. Had she been hibernating?

She was sick a lot. She’d spend whole days in bed, not feeling well, missing entire weeks as the world went by outside. My slight but strong-minded friend would be unable to move for pain for several days, but she put on a brave face.

What I didn’t know was that my friend had endometriosis.

I’d thought I was pretty clued in about women’s health, but I had never even heard of this, often hereditary, condition that women worldwide were suffering from.

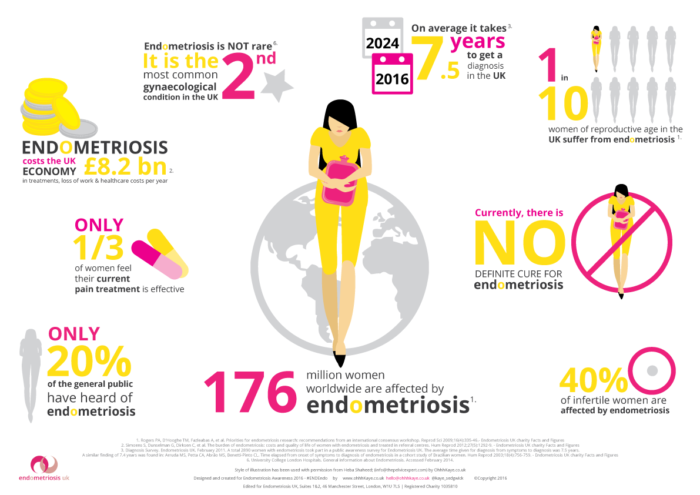

With statements like “researchers think it affects 11% of American women between 15 and 44” (Womenshealth.gov) and “endometriosis affects an estimated 176 million women worldwide” (endometriosis.org), it seems clear that the statistics are based largely on extrapolation and guesswork.

(Image via)

What little is known by health professionals is not common knowledge, and therefore a huge proportion of endometriosis sufferers go undiagnosed and thus untreated. Hardly anyone knows.

But she knew. She had known for years. She knew why she would be floored for several consecutive days every single month of her life. She knew she had to ask favours of friends visiting the USA when she couldn’t buy strong enough painkillers in the UK. She knew because it is a hereditary condition that both her mother and aunt suffered from. The pain was signal enough to tell her what was wrong.

Endometriosis is a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus (the endometrial stroma and glands, which should only be located inside the uterus) is found elsewhere in the body.

The most common symptom of endometriosis is chronic pelvic pain, which often – but not always – correlates with the menstrual cycle.

These women’s physical, mental, and social well-being is impacted by the disease, potentially affecting their ability to finish an education, maintain a career, with a consequent effect on their relationships, social activities, and in some cases fertility. About half of women with endometriosis will also suffer from pain associated with sexual intercourse.

(http://endometriosis.org/resources/articles/myths/)

Due to lack of established medical research, doctors refused to treat her, refused to diagnose her, simply refused to examine her. They heard what she said but would not listen. The more help she tried to get, the more she was pegged as a complainer, a whinge, a hypochondriac.

This is a process experienced by many women with endometriosis, and it makes our healthcare systems look like a joke. Watching a friend go through this rigmarole – the constant misdiagnosis, the recurring failure to take women’s pain seriously, the continued allusion to modern day hysteria – when she was in dire need of serious help, was painful in itself.

Knowing that she knew precisely what was wrong with her but no medical professional would take her seriously was angering, upsetting, and depressing. I couldn’t pretend to understand what she must have felt.

Doctors often recommend that women with endometriosis take the contraceptive pill. My friend had allergic reactions to several varieties of the pill that she was instructed by doctors to try. The only other “cure” that medical professionals continued to offer was to have a baby. The first time she heard this, my friend was seventeen. Way to encourage an intelligent young woman to take charge of her health, NHS!

Sadly, the healthcare system is plagued with myths and misconceptions.

The so-called solutions professionals offered my friend are simply not solutions to her problem at all. Studies show that neither pregnancy nor hormonal treatments cure endometriosis. Other myths surrounding the chronic condition implicate a woman’s lifestyle choices – anywhere from douching to abortion – as the cause of what is actually a hereditary disease.

I cheered my friend up by calling all the awful people in her life “cunts” (a word I had just discovered in earnest), making more tea, and offering a safe space for her to vent her frustrations. But I could not solve her problem.

About half way through our second year of university, she had finally found someone who took her seriously. She had to have surgery simply to find out whether she had endometriosis. She missed the last week of term, spent the entire four weeks of the Christmas holidays recovering in bed, and had to apply for extensions on all her deadlines. She recovered slowly but healthily and things got better. The surgery finally confirmed what she already knew. It helped for a little while, but it did not improve her condition permanently.

Years later, my friend still suffers from endometriosis. Her current “options” are just as bleak: undergo further surgery (where the scar tissue may well be as damaging as the endometriosis itself); have an injection which will throw her into “faux menopause”; or have a hysterectomy at the age of twenty-six!

Years later, my friend still suffers from endometriosis. Her current “options” are just as bleak: undergo further surgery (where the scar tissue may well be as damaging as the endometriosis itself); have an injection which will throw her into “faux menopause”; or have a hysterectomy at the age of twenty-six!

Ria is one of the strongest people I know. She will continue to fight this debilitating condition with her whole self, and she will never give up.

“A woman is like a teabag. You never know how strong she is until you put her in hot water” (attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt).

To find out more about endometriosis, please visit: Endometriosis UK or endometriosis.org.

For more personal accounts, Lena Dunham’s account of her endometriosis is insightful.

If you enjoyed this article, why not check out: ‘The Bloody War: Let’s Get Real About Menstruation!‘?

Tags: endometriosis friendship Joy sisterhood strength women's health

Categories: From the Heart Wise up!